Center of National Integration During the Wei, Jin and the South and North dynasties

After the Eastern Han Dynasty (25BC~220AD), China stepped out of the heyday and entered a period of national division as well as social turbulences in the Wei, Jin and the South and North dynasties (220AD~581AD). During the period from 304AD to 439AD, “Wu Hu” (the five main nomadic tribes in northern China: the Huns, Xianbei, Jie, Di, Qiang ect.) established “Sixteen Kingdoms” which shattered the original political pattern on Guanzhong Plain. Historians named the period as “Wu Hu Chaotic Period” (Cataclysm by the nomadic tribes in northern China).

Among the minority regimes, the Former Zhao State, the Former Qin State and the Later Qin State established their capitals in Chang’an consecutively, while the Great Xia State chose the city of Tongwan as the capital. In addition, the Western Wei State which separated from the Northern Wei State and the Northern Zhou State also chose Chang’an as their capitals. Frequent changes of regimes lasted for many years. Chang’an, as a permanent capital for many dynasties, became the target of attacks. Therefore, in the turbulent days of the history, Shaanxi was in a total chaos. However, with the time-honored culture and traditions, Shaanxi once again fully displayed its importance as a national integration center, a melting pot of different civilizations and a strategic stronghold in China. In the meantime, those historical events paved the way for a national unity in the Sui Dynasty and prosperity in the Tang Dynasty.

The development of China’s civilization is a national integration history and among which the Wei, the Jin and the South and North dynasties (220~581AD) consisted of the most important chapters. Throughout the period, as a power center, Shaanxi turned itself into a huge national integration stage which led to a happy reunion.

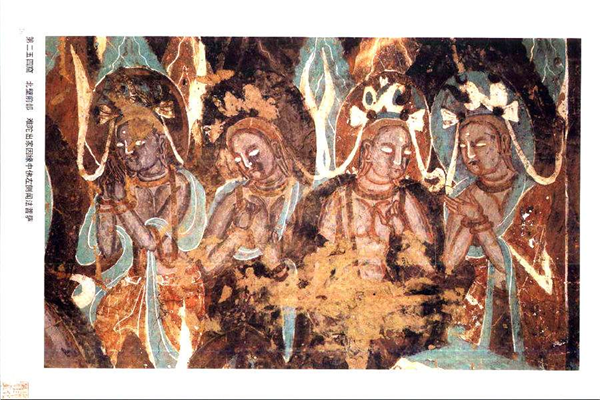

Back to the Western Han Dynasty, ethnic groups started moving into Shaanxi area, particularly in Guanzhong Plain. From the Eastern Han Dynasty to the Western Jin Dynasty (25~316AD), the ethnic groups like Di and Qiang took up more than half of the population in Guanzhong Plain which had never happened over a long period of history. It is mainly the people of Di and Qiang nationalities who came to Guanzhong Plain from the Western Han Dynasty to the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty (206BC~220AD). More and more people of Huns and Tygtr came to Guanzhong Plain in the “Sixteen States Period”. When it came to the Northern Dynasty (386~581AD), it is mainly Xianbei who came to Guanzhong Plain. There were also Ba People in southern Shaanxi at the same time. Many people from the Western Regions also came to Guanzhong Plain at that time. According to records, more than 2,000 people from Kangguo (Samarkand) came to Chang’an before the Former Qin State and settled in Lantian County (in the southeastern part of Guanzhong Plain). In the Northern Zhou Dynasty (557~581AD), people from Sogdiana were even appointed high-ranking officials by the government. The excavations of the tombs of the Sogdians proved the influx of Sogdians to Chang’an. The newly-found relics manifest the perfect blend of the Western and Eastern cultures which fully demonstrate that Shaanxi was more than an integration center for many ethnic groups in ancient China; it was also a melting pot for cultural exchanges.

National integration started from imitating and learning from the Han nationality by the ethnic groups and eventually people from different ethnic groups were assimilated by the Han nationality. Hence, the integration was a process of localization. The defining feature was reflected on their adoption of the Han surnames. Upon their arrival, people from ethnic groups either had no name or used the surnames of Hu. Three tablets exhibited in Beilin Museum (The Museum of the Forest of Stone Tablets), namely Tablet for Military Officer Deng, Tablet for General Guangwu and Tablet for Hui Fu Temple are not only renowned calligraphic tablets but also important material to show the evolution of the surnames of ethnic groups. Three tablets fully display ethnic groups’ upward spiral of localization. There were many records of people with their surnames of the Qiang, Di and Tygtr nationalities on the first two tablets which reflected that people were not embarrassed by their minority surnames but instead they showed pride and honor for their surnames—at least better than no surname. However, when it came to the Northern Wei Dynasty (386~557AD), heavily influenced by Emperor Xiaowendi’s localization policy, people of minorities, particularly the upper class replaced their minority surnames with the Han surnames instead. The temple tablet of Huifu records a person named Wang Qing, his real name was Wang Yu—the imperial official under the rule of Emperor Xiaowendi who came from Qiang minority group. Qiang, together with Lei, Dang and Fumeng were big surnames in ethnic groups. However, after gaining a higher social status, he chose to use a surname from the Han nationality rather than the surname of Qiang. The surname Wang enjoyed a good reputation in China; the change of the surname converted his nationality. Although his name wasn’t recognized by the public, it fully revealed minority peoples’ mentality of integrating themselves into the Han nationality. These stone tablets reflect the procedure of surname changes of the national minorities over decades. And the change was divided into several stages. The change itself tells us how the minorities at that time altered their surnames. As a result, people surnamed Qianer gradually changed their surname to Wang and then surname Qianer disappeared. Interestingly, a pursuit of the typical and standard surnames like Zhang, Wang, Li made these surnames on the top of the surname list for the Han People.

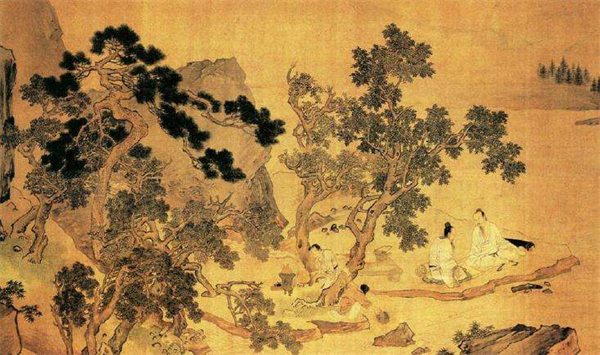

In the Northern Zhou Dynasty (557~581AD) and the Sui Dynasty (581~618AD), the localization of customs and habits of the minorities was already completed in Guanzhong Plain. The prohibition of marrying the descendants of national minorities was lifted which made it possible for Yang Zhong and Li Bing to marry the two sisters under the surname of Dugu. People of ethnic groups were also allowed to take important posts in the imperial court; it was an open secret that no one seemed to have the interest to find out or to tell who was Han and who was not.

People now can not tell the nationality of the supreme ruler surnamed Yuwen of the Northern Zhou Dynasty (557~581AD). After the Tang Dynasty (618~907AD), the surnames of the five ethnic groups vanished from the central part of China. If we read the family pedigrees of the people in Guanzhong Plain, we may find that their ancestors used to be national minorities and they had their minority surnames. Later they changed their surnames into the surnames used by the Han People. If you don’t read their family pedigrees, you will never know their original surnames.

Many minorities were assimilated by the Han People in ancient China. At the same time, their own culture was also integrated into the culture of the Han nationality. It was like influx of fresh blood for the Han nationality. Hence, the Han nationality brimmed with more vigor and vitality. This change is a must of history and serves as a significant and far-reaching transformation. The Sui and Tang dynasties are the heydays of China’s feudal society; China achieved the prosperity with unprecedented vigor and high spirit in the two dynasties. Thanks to the national integration and cultural exchanges during the Wei, the Jin and the South and North dynasties (220~581AD), China took the leading position in politics, economy and culture in the world at that time.